Our History

Stanford Sierra has taken many forms throughout its history, culminating in the family camp and conference center that are thriving today. This place has been shaped by ice, Indigenous people, John Steinbeck, stagecoaches, Stanford University, and families from across the nation.

The land itself was carved during the most recent ice age, when a large glacier slowly moved through the Glen Alpine Valley, creating Fallen Leaf Lake and depositing the moraines you can see along the Angora and Cathedral ridgelines.

The Washoe people are the original inhabitants of Da ow ag a (the Lake Tahoe area). Tahoe is a mispronunciation of Da ow, meaning “lake.” Washoe ancestral land consists of a nuclear area with Lake Tahoe at its heart and a peripheral area that was frequently shared with neighboring tribes. Washoe people have adapted and integrated their cultural practices and continue to reside within the Lake Tahoe basin.

The Washoe people feel that it is vital for all residents and visitors to understand the depth of Washoe history as well as the current status of the Washoe sovereign tribal nation. This knowledge will help to form a more respectful and complete understanding of the lands and people of Lake Tahoe and the surrounding areas. Today the Washoe people continue to act as stewards of the Lake Tahoe Basin and request that we assist in preserving this environment to benefit future generations.

Setting up Camp

Euro-American settlement in the Lake Tahoe region began in the mid-19th century with an influx of Gold Rush miners. In 1897, William Wightman Price arrived at Fallen Leaf Lake. An early Stanford graduate (Class of 1897, MA ’99), Price was an ornithologist and a long-time nature enthusiast. He built a boys’ camp upstream from Fallen Leaf Lake, near Glen Alpine Springs. At Camp Agassiz, the boys learned to fish, hunt, and live in the outdoors. They climbed the mountains, measured the trails with bicycle wheels, and installed plaques at the top of peaks so hikers could record their visits.

William Wrightman Price

When Price married and brought his wife, Bertha, Class of 1894, to the camp, the boys’ relatives decided it was permissible for “outsiders” to visit. At nearby Glen Alpine Springs Resort, the proprietors were a bit unhappy that people were staying at the camp instead of their hotel. The story goes that one day there were 75 visitors at the camp and the resort owners informed Price that they would no longer carry milk and mail for a competitor. Price moved his business to the south end of the lake, where it became Fallen Leaf Lodge.

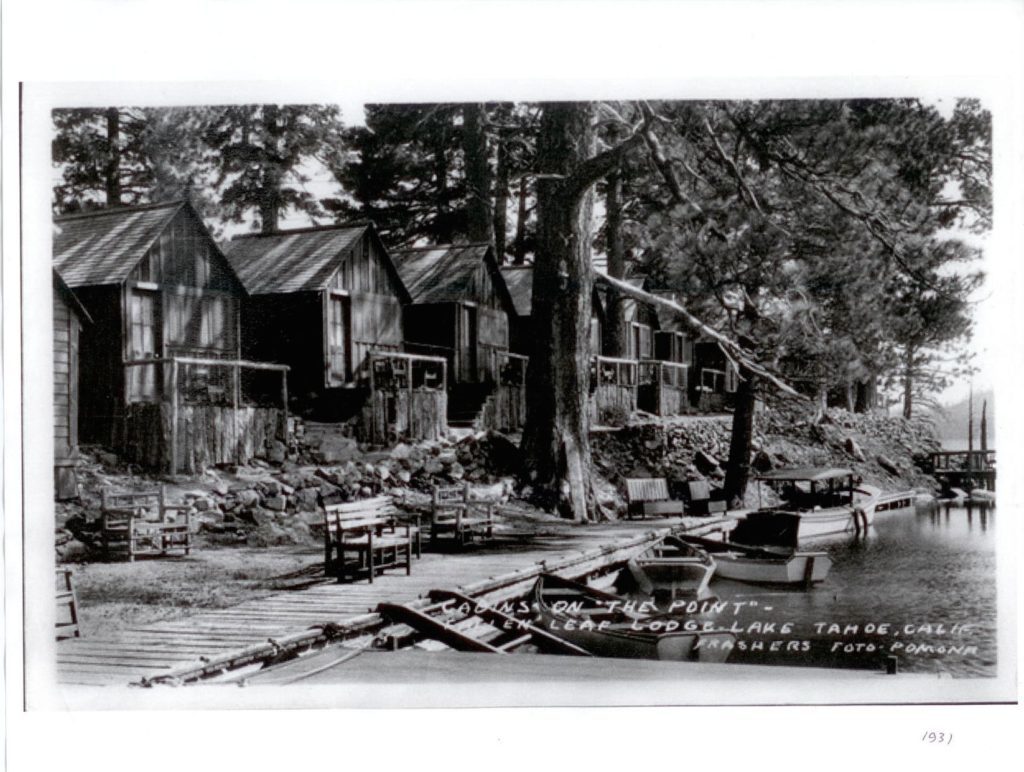

Cabins On The Point – Fallen Leaf Lake Lodge (1931)

By 1907, the Prices were building summer cabins, including many of the current-day staff cabins along “Rustic Row” and on the Point, as well as Cherry Cottage, the current director’s residence and the oldest cabin on Fallen Leaf Lake. The group of cabins became a favorite summer spot for friends of the Prices—many of whom were Stanford professors.

In 1925, Bertha Price journeyed to Palo Alto to inquire about one Toby Street, the roommate of then–Stanford undergraduate John Steinbeck (and the intended of one of Price’s employees). Steinbeck so charmed Price that she hired him to perform maintenance work and shuttle guests. He wrote his first novel, Cup of Gold, during a snowy Tahoe winter.